How Pope Leo Faced Corrupt Politicians and Economic Collapse in Peru — and Built Hope Instead

Long before he was Pope Leo XIV, Fr. Roberto Prevost learned what real power in the fact looks like: presence, patience, and courage.

Dear friends —

Happy Sunday!

Thanks to your incredible support, Letters from Leo continues to be one of the fastest-growing Substacks in the world — and a space open to everyone, no matter your politics or your faith.

Today, we continue our journey into the “hidden years” of Pope Leo XIV — the period that shaped his heart, his theology, and ultimately, his papacy.

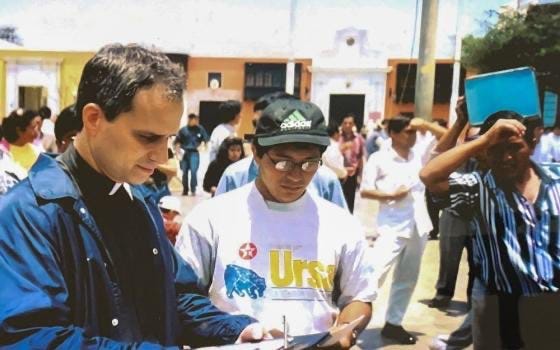

Part II, today’s essay, turns to the crucible that followed — the years of Peru’s economic collapse, political turmoil, and internal war, when Fr. Roberto’s quiet presence became a lifeline for his people.

Through hunger, blackouts, and fear, he helped build a Church that listened, accompanied, and held its community together — a “living network of solidarity,” as his friend Armando Jesús Lovera Vásquez recalls in his extraordinary new book about Leo’s time in Peru.

Part III, coming soon, will trace the through-lines from Trujillo to the papal ministry — how those years among the poor in northern Peru still echo in the decisions and gestures of Pope Leo XIV today.

These essays take time and care to produce — grounded in both faith and history — and, like all longform reporting here about the life and formation of Pope Leo XIV, are available exclusively to paid subscribers.

If you’re already subscribed but can’t access this piece, just reply to this email and we’ll fix it right away.

Thank you, as always, for walking this road with me.

In 1990, Peru’s economy imploded as President Fujimori’s drastic shock measures sent prices sky-high overnight.

“If before we had poverty, now we had despair,” Lovera recalls of that time. Government safety nets were non-existent: “the State had nothing to respond to the emergency it had created.”

In this void, it was the Church that stepped forward as the backbone of social survival.

Not through grand episcopal statements or lofty homilies, Lovera notes, but through the concrete and the human.

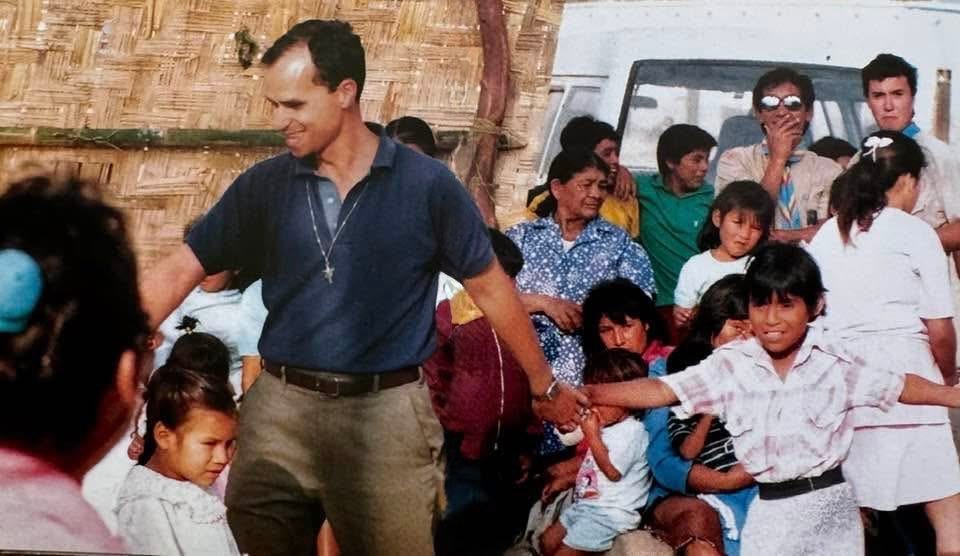

In parishes like Fr. Roberto’s, the Church became “the face, hands and feet of solidarity.”

Caritas Peru mobilized donations of food and medicine from abroad, but it was the local communities — parish volunteers, youth groups, mothers’ clubs – that distributed everything on the ground.

“The idea wasn’t just to hand out food; it was to respond with intelligence and tenderness,” Lovera explains.

Everyone was involved — no one made to feel like a mere charity case.”

No one felt only a beneficiary; we were all part of the solution… all in need, yet all able to share,” he writes.

On some days the parish courtyard literally became a warehouse, with sacks of rice and powdered milk piled high.

But “it wasn’t charity — it was something else. A living network, a community that suffered together but also held itself together,” Lovera emphasizes.

People shared the little they had with those who had nothing, in a contagion of generosity few had ever seen before.

Here’s how the future pope played a key role in all of this.