The American Pope: How Leo Rose — And How We Misunderstand Him

Get the backstory from Vatican insider Christopher White — and claim your free book with a year-long subscription.

Dear friends,

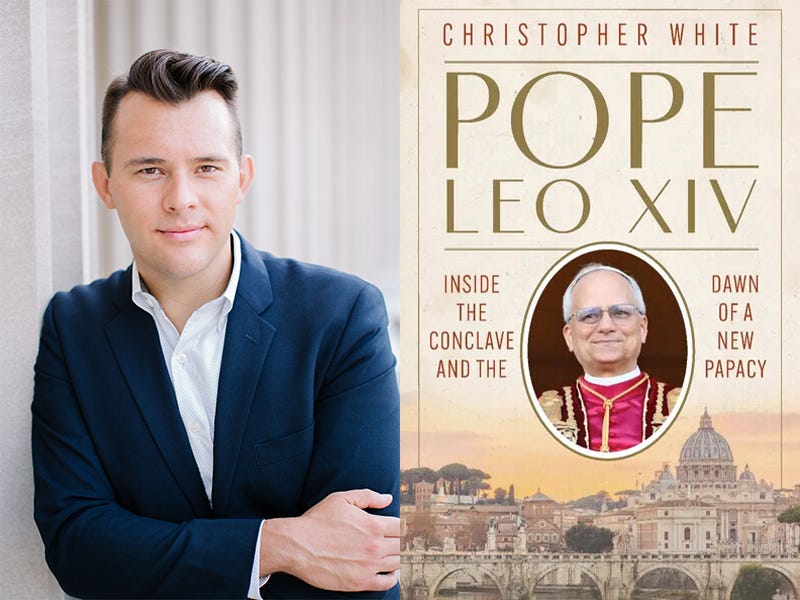

Today, I had the honor of interviewing Christopher White about his new book, Pope Leo XIV: Inside the Conclave and the Dawn of a New Papacy.

I can personally attest that it’s a remarkable read — and the most definitive account yet of Robert Francis Prevost’s historic election as Pope Leo on May 8.

Letters from Leo exist solely because of your generosity. If you find value in my work, please become a paid subscriber today.

Subscriptions start at just $6.67/month, and include full access to:

My ongoing series on Faith and the Democratic Party

The multi-part deep dive into Pope Leo’s life and formation

The latest installments:

Part IV (published Sunday) explores Pope Leo’s 20-year friendship with Pope Francis.

Part V (published Wednesday) profiles his closest cardinal confidant, Luis Antonio Tagle.

Do you prefer a one-time gift? Donate here instead of subscribing.

Christopher White is one of the most respected Vatican correspondents alive today. His new book, Pope Leo XIV: Inside the Conclave and the Dawn of a New Papacy, is the definitive account (so far) of the fastest rise to the papacy in modern history—and the global shockwaves it has already begun to send.

In this email interview for Letters from Leo, we talk about Pope Leo's political instincts, his relationship to the United States, the temptation of wishcasting progressivism onto the Vatican, and what it means to confuse the papacy with a presidency.

Christopher’s answers have been lightly edited for clarity.

1. At the Jubilee for the Youth Vigil, Pope Leo gave what many are calling his first truly off-the-cuff remarks—and there was a noticeable shift in tone: more emotive, more empathetic. Pope Francis once spoke of the “grace of office,” saying it transformed him from an austere cardinal into a more outwardly joyful pope. It’s only been three months, but do you see that same transformation beginning to take shape in Pope Leo?

Francis was an extrovert — like Pope John Paul II before him, he came to view the papacy as a global stage and often led through symbolic gestures: traveling to warzones, bringing Syrian refugees back with him to live in Rome, even paying his own hotel bill. It’s a long list.

Leo is an introvert by nature — a man of discipline and management, which is part of why he was elected. As I chronicle in my book, the cardinals chose him in large part because they wanted someone who would continue Francis’s pastoral priorities and strategically implement them in a way that could bring the whole Church on board.

In the book, I draw a comparison to the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), when the Church opened itself to the modern world. Pope John XXIII was the visionary who initiated the council; after his death, Pope Paul VI was elected to carry out those reforms. I think it’s unlikely Leo will be as spontaneous as Francis — it’s simply not in his nature — but I do think we’re already seeing him grow more comfortable in the role.

When I first met him after he arrived in Rome, I was struck by his gentleness and thoughtfulness, but it was also clear that he resisted the spotlight. That’s still true — but now we’re seeing a growing charisma and a recognition that he is speaking to the world, in both word and deed.

2. A lot of my readers are secular progressives. In your view, how will Pope Leo resonate with them—and where will he inevitably disappoint? And what are the risks of progressives projecting their own values onto a figure who still leads a fundamentally conservative institution?

One of Pope Leo’s Augustinian confreres, whom I interviewed for the book, predicted that Leo will frequently delight conservatives and occasionally disappoint them — and frequently delight progressives and occasionally disappoint them. I think he was getting at something important: like Francis before him, Leo will champion human dignity and the common good. That will lead him to stand with migrants and refugees, demand action on climate change, and oppose both abortion and capital punishment.

To use Catholic language, that’s the consistent ethic of life — and neither political party fully embraces it.

Francis often pleaded for the Church to be open to all (“todos, todos, todos”). Cardinal Prevost, before he became pope, said he had personally benefited from Francis’s emphasis on inclusion. So it’s no surprise that, in his first speech from the balcony on May 8, Leo called for a missionary, bridge-building Church that is open to everyone.

3. Your book brings Pope Leo’s meteoric rise to life — he went from cardinal to pope in just eighteen months. One of Pope Francis’s final moves was elevating him to cardinal bishop, the Church’s highest rank. Do you think Francis saw Leo as his successor? And if Jorge Mario Bergoglio had cast a vote in the 2025 conclave, who do you think he would’ve chosen?

I wouldn’t go so far as to say Francis was trying to influence the conclave, but it’s clear he did everything in his power to elevate Robert Prevost’s profile.

Leo went from being a relatively unknown bishop in Peru to running one of the Vatican’s most powerful departments. Then, just months before his death, Francis elevated him to cardinal bishop — the highest rank among cardinals. That’s an extraordinary ascent in Church life, and I think it shows the deep respect Francis had for Prevost. He clearly saw him as a man of integrity who embodied the kind of leadership he hoped to see more of in the Church.

4. Pope Francis famously never returned to Argentina after his 2013 election. In your book, you explore Pope Leo’s dual American and Peruvian roots. From his early gestures and words, it seems he may feel as much — if not more — affinity for Peru than for the United States. Do you think Pope Leo will visit the U.S. as pope? And if so, would he do it while Donald Trump is still in office?

I wouldn’t say Leo feels more affinity for Peru than the United States — it’s just a different kind of relationship. He was named bishop of the Chiclayo Diocese in Peru, and that comes with a special pastoral obligation. He was — and remains — their shepherd. That’s a unique and lasting connection.

Leo has also credited Peru with teaching him how to be a priest — how to walk alongside people in the daily struggles of life. That experience forged a permanent bond he still carries.

Francis, as we know, never returned to Argentina during his twelve-year papacy. Personally, I’ve always found that rather sad. But he didn’t want a papal visit to be manipulated by politicians, and there never seemed to be an ideal moment given the country’s instability. And of course, over time, his health declined.

Leo is 69 — young for a pope. He will certainly visit the United States, but he’ll do so on his own timeline, at a moment when he believes the visit will have maximum impact for both the Church and the country. Right now, he has a trip planned to Turkey later this year for a major ecumenical gathering. I suspect Latin America may come next. A U.S. visit will follow — but only in consultation with Church leaders here, not based on election cycles.

That said, I just returned from launching the book in his hometown of Chicago — and the excitement for a visit from “da Pope” was palpable everywhere I went.

5. I’m often criticized for seeing the Catholic Church too much through a political lens. But for the readers of this Substack — many of whom come from political worlds — what’s the clearest way to understand the difference between a pope and a politician? Where do they overlap, and where must we resist the temptation to conflate them?

Pope Francis wrote a remarkable letter in 2020 called Fratelli Tutti (“Brothers and Sisters, All”), where he called for “a better kind of politics.” He urged Catholics to engage politically, especially on behalf of the vulnerable, and to foster global solidarity. But he also warned against becoming captive to partisanship or compromising core principles for political gain.

Leo has echoed many of these themes in his early days. A pope holds no military or economic power — but he does wield an enormous moral platform. He can speak to issues of global consequence not as a politician counting votes, but as a moral leader focused on the common good. And that gives him extraordinary freedom.

In an age where the lines between religion, politics, and performance are increasingly blurred, Pope Leo XIV remains a singular figure—both deeply traditional and surprisingly modern.

Christopher White’s book offers a front-row seat to the making of a pontificate still unfolding—and to the complex man now sitting on the Chair of Peter.

You can find Pope Leo XIV: Inside the Conclave and the Dawn of a New Papacy wherever books are sold.

And if this conversation challenged or confirmed your view of Pope Leo, let us know in the comments — because he just might be reading.

Letters from Leo exist solely because of your generosity. If you find value in my work, please become a paid subscriber today.

Subscriptions start at just $6.67/month, and include full access to:

My ongoing series on Faith and the Democratic Party

The multi-part deep dive into Pope Leo’s life and formation

The latest installments:

Part IV (published Sunday) explores Pope Leo’s 20-year friendship with Pope Francis.

Part V (published Wednesday) profiles his closest cardinal confidant, Luis Antonio Tagle.

Do you prefer a one-time gift? Donate here instead of subscribing.

What, I know about, Pope Leo ♌️, so far I do like. God Bless, you Chris.

I am a secular fan of Pope Leo. He has already both amazed and disappointed me, but not as much as some high stakes figures in the daly news! (You know who I mean). I eagerly read about his life and am uplifted by his desire to bring people together. I love how he emphasizes empathy and kindness. As a fellow introvert, I admire his ability to handle his position with grace and an open heart. THANKS for your wonderful post.