Q&A: Fr. James Martin on Failure, Faith, and Finding God at Work

The Jesuit priest reflects on how ordinary jobs, early mistakes, and unglamorous labor shaped his conscience, compassion, and understanding of God’s presence.

Dear friends —

Every once in a while, a conversation slows you down.

Not because it offers easy answers or tidy resolutions — but because it forces you to look again at the parts of your life you’ve already rushed past. The jobs you thought were dead ends. The mistakes you still wince at. The seasons where God felt distant, silent, or entirely absent.

That’s what this conversation with Fr. James Martin did for me.

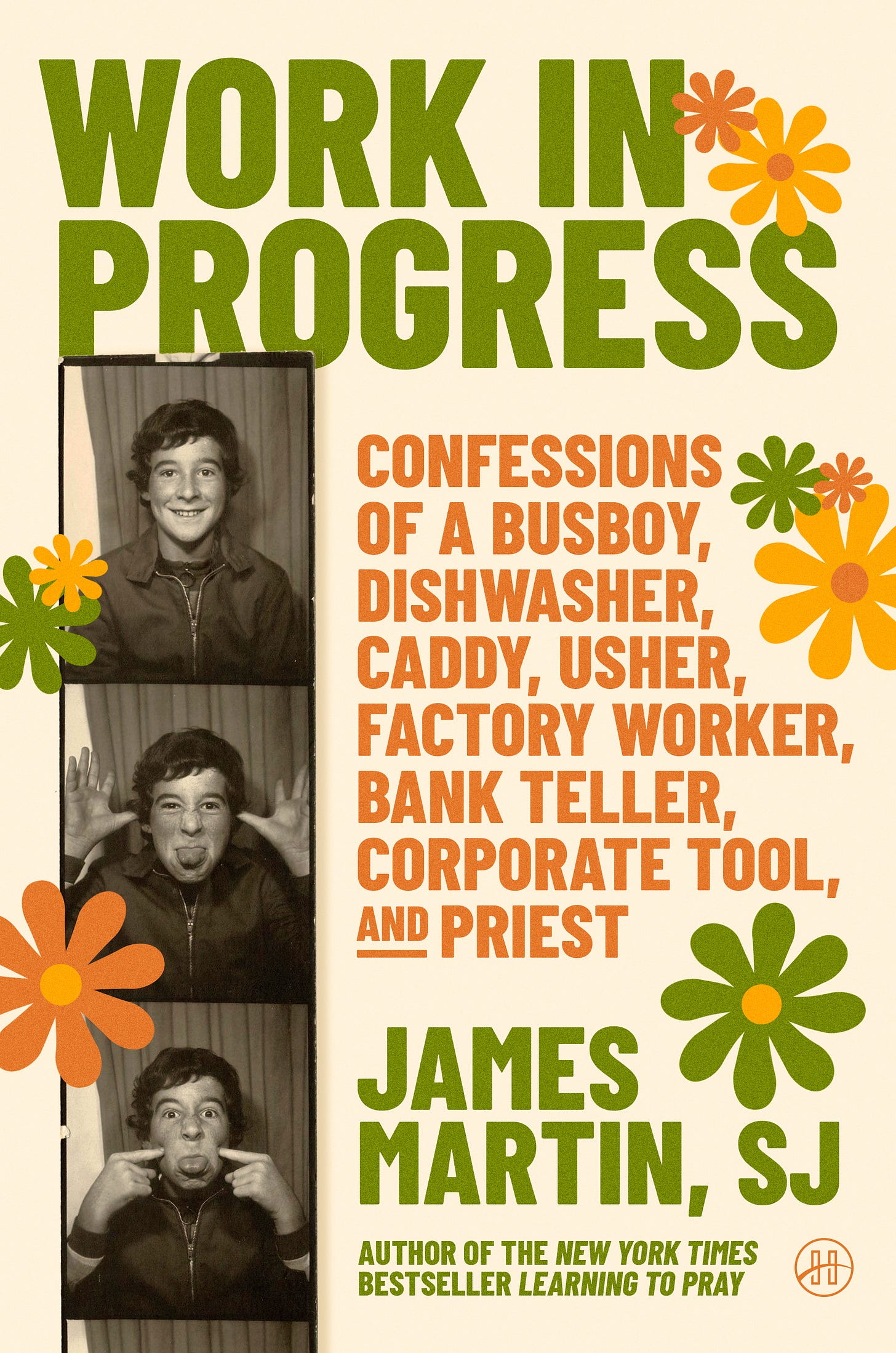

In his new memoir, Work in Progress, Fr. Martin reflects on the ordinary, often unglamorous labor that shaped him long before he became a Jesuit, a priest, or one of the most recognizable Catholic voices in the public square. Busboy. Dishwasher. Lawn-mower. Assembly-line worker. Stock brokerage trainee.

Jobs marked not by prestige, but by repetition, fatigue, embarrassment, and failure.

What emerges is not a sentimental nostalgia for “humble beginnings,” but a bracingly honest account of how God forms consciences in places we’re trained to dismiss — and how spiritual clarity often arrives years after the fact, once we finally learn how to notice.

In this interview, Fr. Martin speaks candidly about growing up largely unaware of God’s presence, about his early hunger for approval, and about the slow, sometimes uncomfortable work of learning to see God “in all things.”

He reflects on how manual labor sharpened his sense of justice, exposed the limits of unregulated capitalism, and grounded his later commitments to solidarity and compassion. And he’s refreshingly direct about failure — not as something to be avoided at all costs, but as one of the primary tools God uses to form us.

At a moment when our culture is obsessed with optimization, status, and résumé-building, Work in Progress offers something countercultural: the insistence that nothing — not even the jobs you hated, the mistakes you regret, or the ambitions that collapsed — is wasted.

This conversation is about work, yes. But it’s also about attention. About listening for God’s voice amid noise and anxiety. About learning to recognize grace in hindsight. About the quiet disciplines — like the daily examen — that help us discern meaning in lives that feel anything but extraordinary.

Before you dive in, one important note for readers:

Anyone who purchases a yearly subscription to Letters from Leo or donates $80 or more from this post will receive a brand-new copy of Fr. James Martin’s Work in Progress.

This offer is available until February 11 at 11:59 PM EST.

If you’ve been considering joining our community, this is a good moment to do it — and to read a book that might help you reinterpret your own story with more honesty, mercy, and hope.

Paid subscribers have access to the Sunday Scripture Reflection Series, our new investigative series on Jeffrey Epstein and Steve Bannon’s attempt to take down Pope Francis, the Q&A mailbag that opened recently, where you can ask me anything about American politics, Catholicism, Donald Trump, Pope Leo, JD Vance — or my own faith, biography, and life.

Letters from Leo is open to anyone who wants to be informed and inspired by our pope — and to turn that inspiration into action that leaves America and the world more just, less cold, and more alive with hope.

If you’d like to invest in our mission, here are three ways you can help:

Subscribe as a paid member to receive exclusive posts about the life and formation of Pope Leo and help sustain this newsletter.

Donate with a one-time gift to fuel this project’s mission.

Share this post (and Letters from Leo) with a friend who might enjoy it.

Whether you give $0, $1, or $1,000, your presence here matters — no matter your faith or your politics.

Thank you for reading. I’ll see you on the road.

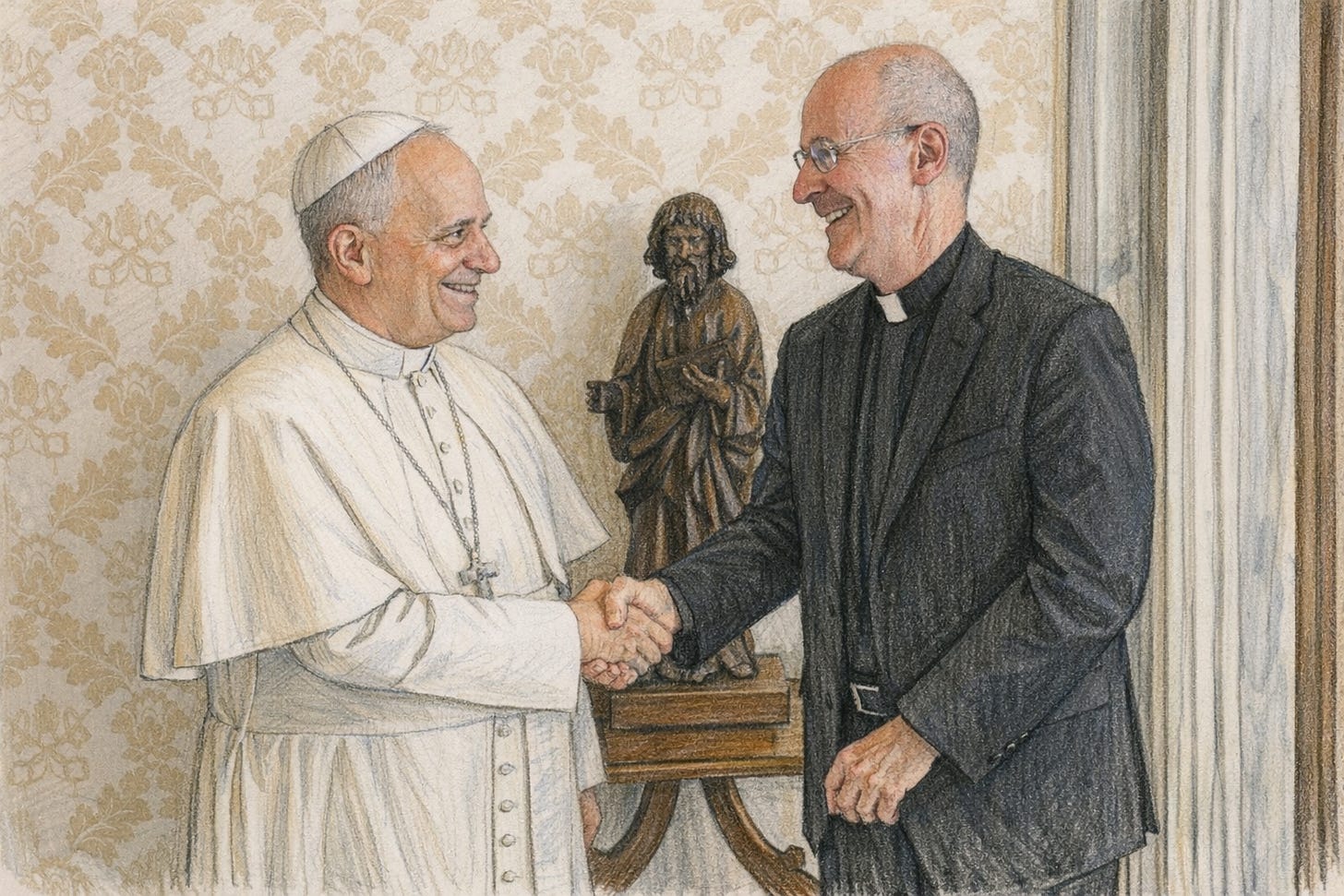

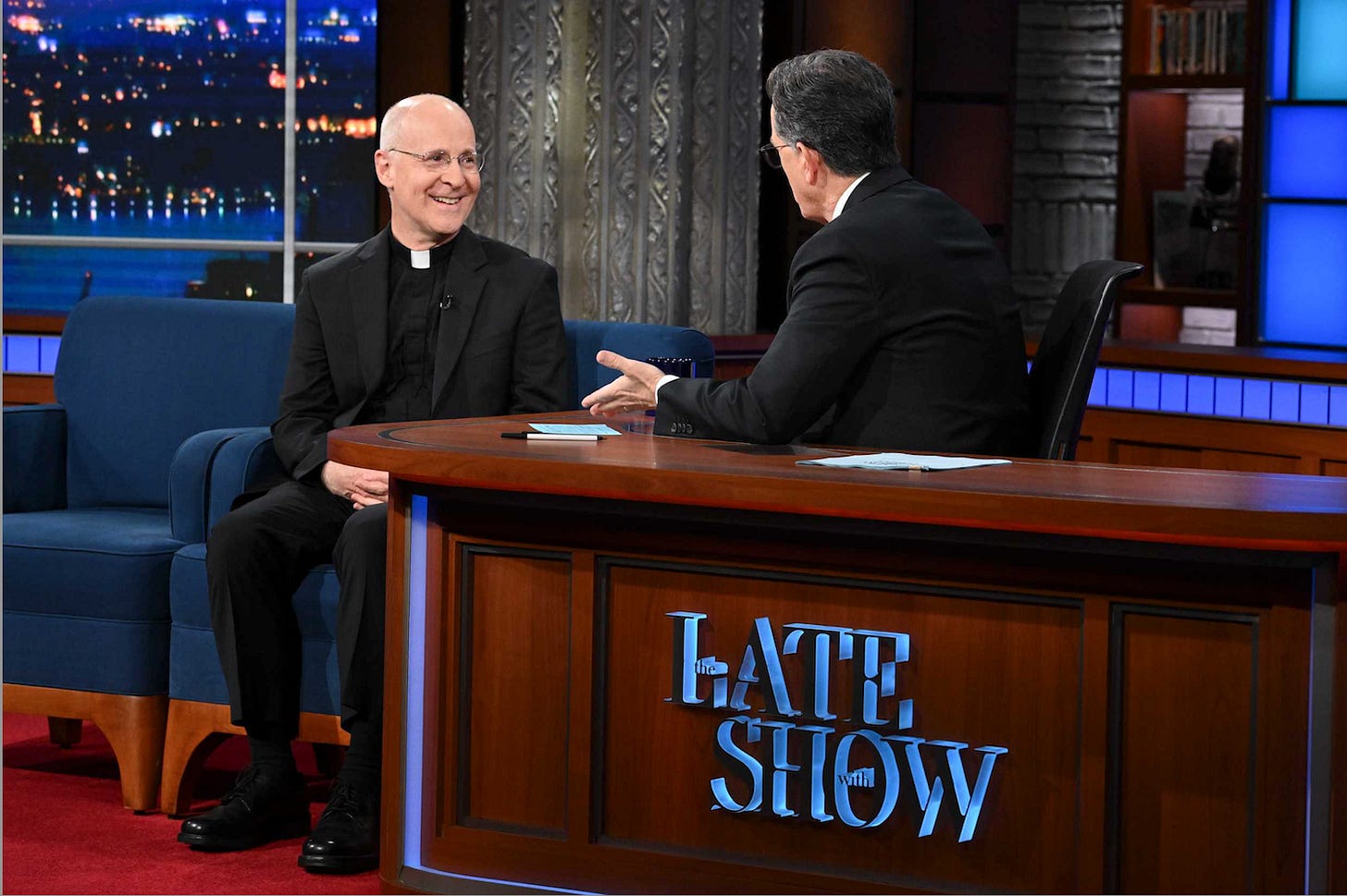

Fr. James Martin is one of the most recognizable Catholic voices in American public life today — arguably the most beloved Catholic evangelist since Bishop Fulton Sheen brought the faith to television audiences in the 1950s and 1960s.

His new memoir, Work in Progress, is a disarming, quietly radical account of how God forms us not through prestige or success, but through ordinary work, failure, and the long apprenticeship of paying attention.

In this interview for Letters from Leo, we talk about Fr. Martin’s early jobs and bruised ego, learning to notice God’s presence years after the fact, how manual labor shaped his conscience and critique of capitalism, the spiritual value of failure, and what it means to discern God’s call in a culture addicted to noise, anxiety, and status.

Fr. Martin’s responses have been lightly edited for clarity.

Your memoir blends humorous and humbling early job experiences with profound spiritual reflection — how did your perception of God’s presence evolve as you transitioned from seeking approval to embracing work that felt routine or even disheartening?

As a boy and a teenager, I was only dimly aware of God’s presence — if at all. The notion that God would communicate with me seemed, as I say in the book, either arrogant or delusional. Or both! There was one powerful moment of God’s presence that I experienced as a boy, also described in the book, but the recognition that it might be God didn’t come until much later.

What happened was not so much that I stopped seeking approval or even started to embrace work. Rather, what happened was that once I joined the Jesuits, I was encouraged to notice God in all things. Then, looking back, I was able to see more clearly where God was — even in some of the crazy summer job experiences that I describe in Work in Progress. So those jobs — busboy, dishwasher, caddy, lawn-mower, movie-theater usher, and so on, taught me a great deal, but were also suffused with God’s presence. But I didn’t notice that until years later.

You candidly discuss how ordinary labor shaped your conscience and deepened your compassion, even critiquing the flaws of unregulated capitalism. How do you think those lessons can inform the Church’s approach to economic justice today?

Most of the summer jobs I held down, until the last two years of college--when I was a bank teller and worked in a stock brokerage--were manual labor. So I worked alongside people who were not financially well off and sometimes even quite poor. And I saw first-hand how they were sometimes treated by managers, which was, especially during my time as an assembly-line worker, like cogs in a machine.

But, more broadly, some of what I was taught as an undergrad at Wharton, when we learned about the “transitional poor,” that is, people who were only “temporarily” poor until the rising economic tide lifted their boats, was disproved by walking around West Philadelphia. There I saw people whom capitalism had failed. What I eventually realized was that even if capitalism is the most efficient system for distributing goods and services, it’s not perfect. It needs regulation and society needs a safety net.

Reflecting on your journey, what role did failure — whether in vocation or self-perception — play in shaping your heart for the priesthood? How should Christians today view failure in their own vocational paths?

In all my summer jobs, I made a lot of mistakes — some funny, some not! —but at the time I was reluctant to admit that. As I say in the book, I was almost allergic to apologizing, since it offended my ever-expanding teenage ego. One of the lessons of the book, then, is that no one’s perfect: it’s okay to make mistakes; apologizing is necessary; and it’s okay, especially at the beginning, when you’re learning, to ask questions.

All of us can learn from these kinds of early job experiences. None of us is perfect after all, so we’re all going to make mistakes. The key is learning from them. This is one way that God is able to, as we say in religious orders, “form us,” whether you’re a busboy, a waiter, a mother, an attorney, a teacher, or even a priest.

Your book highlights that nothing in your life was wasted. In a society fixated on success and status, how can individuals discern God’s call amid the noise of anxiety, distraction, and worldly ambition?

That’s a big question! First, by noticing. So much of God’s voice in our lives is quiet, subtle, even mysterious. In the midst of noise and anxiety and distraction, it helps to simply notice the signs of God’s presence. And one of the best ways to do that is the prayer called the “examen,” when you look back on the day. It’s often easier to see God in the past than in the present. That’s something I learned from my own life and talk about in the new book. God’s everywhere in your past. You just have to notice.

In an age obsessed with status, optimization, and visible success, Fr. James Martin offers something quietly subversive: a spirituality rooted in ordinary labor, honest failure, and the long work of learning how to notice God’s presence after the fact.

Work in Progress is not a memoir about arrival. It’s a memoir about formation — about how consciences are shaped in kitchens, stockrooms, assembly lines, and awkward apologies; about how God wastes nothing, even the jobs we’d rather forget.

Father Martin’s new book is currently available wherever books are sold.

If this conversation resonated with your own experiences of work, failure, ambition, or discernment, I’d love to hear from you in the comments. These are not abstract questions — they’re the raw material of most of our lives.

And if you’re considering joining Letters from Leo, remember: anyone who purchases a yearly subscription or donates $80 or more from this post will receive a brand-new copy of Work in Progress.

The offer lasts until February 11 at 11:59 PM EST.

Sometimes the holiest thing we can do is look back — and realize God was there all along.

Thank you for the article, Chris, most of my summer jobs were because of the comprehensive employment training act signed by our beloved, President James E. Carter. It taught me to respect hard work and my parents were very pleased about the fact their children were learning respect and dignity for the working men and women of America. This money helped me purchase two vehicles, vehicles, pay for gasoline to put in the cars and made sure the oil was changed. It helped me respect my self and others around me. My prayers to Pope Leo ♌️ and Holy Mother Church of cardinals .

I have been a fan of James Martin since he wrote My Life with the Saints. I love the way he shares his life and explains his faith. He is a real gift to the church.